An Intro to Python

The Pythonic Way!

This is going to be a very opinionated talk

Sorry, not sorry.

But I want it to be interactive

So feel free to interrupt

Your questions are more important than my slides

About Me

Mike Noseworthy

Core Engineering Team - Analytics/ML

B.Eng Computer Engineering - 2012

Writing Python code for 7 years professionally

Table of Contents

- Python Overview

- What Do I mean by "Pythonic"

- PEP8

- The Zen of Python

- Mike's Recommended Python Setup

- Batteries Built-In

- Questions

- Resources

Python Overview

Who...

uses Python daily?

has been using Python for 1 month?

has been using Python for 1 year?

has been using Python for 5 years?

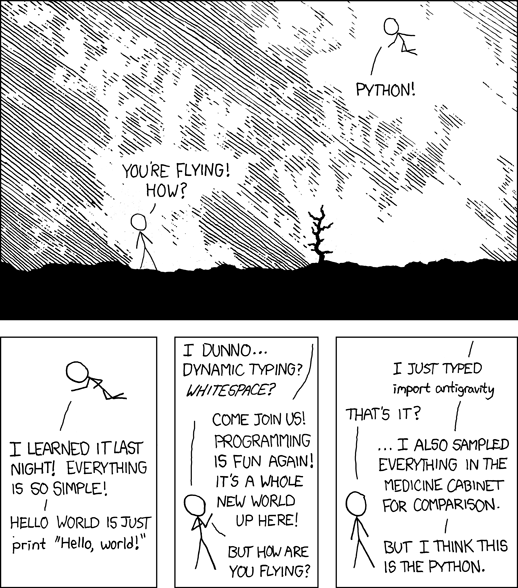

I ❤️ Python

Hopefully you'll love it too!

Regardless of experience, I hope you learn something and have fun!

BDFL* ❤️

Python is...

Named after Monty Python

A little silly

28 years old

Python 3 is 10 years old! 🎉

🦆 Typed

If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.

But still...

Strongly Typed

General Purpose Programming Language

With OO and Procedural Features

Python is a language Specification

But there are different implementations

- CPython*

- PyPy

- Jython

- IronPython

- etc...

Compared to Java

Python 3.7 language spec == Java 9 language spec

CPython Interpreter == OpenJDK implementation of JVM

Generally people just say "Python" and mean CPython

Terms

module- An organizational unit of python code (usually a

.pyfile) package- A module which can contain submodules, or subpackages

(usually a directory with a__init__.pyfile)

Terms ctd.

dunder- Short for "double underscore"

- PyPI

- Python Package Index (or Cheese Shop) - Like maven, apt, cpan, etc. repositories

pip- "

PipInstalls Packages" - Package manager

Importing Packages

The python import statement can be confusing

It finds and loads python modules and packages.

import foo

from bar.baz import shrubbery as shrubFinding Packages

sys.modulesbuiltinsys.path

Finding Packages - ctd.

Example sys.path

>>> import sys

>>> print(sys.path)

[

"",

"~/.pyenv/versions/3.7.3/lib/python3.7",

"~/.pyenv/versions/3.7.3/lib/python3.7/lib-dynload",

"~/.pyenv/versions/3.7.3/lib/python3.7/site-packages"

]Loading Packages

The finder returns a module spec to the loader

The loader loads the module into the local namespace

Loading runs the module or package!!

Loading Example

Let's load my_package

my_package

├─ __init__.py

├─ submodule.py

└─ util.pyLoading Example - ctd.

Contents of __init__.py

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""Init file of my_package"""

print("Hello there!")

Now let's import it!

$ python

>>> from my_package.util import do_calculation

Hello there!

>>>Project Structure

Just do this:

packagename

├─ src

│ ├─ packagename

│ ├─ __init__.py

│ └─ ...

├─ tests

│ └─ ...

├─ docs

│ └─ ...

├─ README.md

└─ setup.pyApplication or Script Entry Point

If you're building an application or script you need a "main" right?

packagename/src/packagename/__main__.py

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""Main entry point for my script!"""

from third.party.package import thing

def main():

"""Main function running appliation loop"""

running = True

while running:

do_stuff()

thing(1, 2)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

"Pythonic" Python

Pythonic Means

Using the features of the language in an idiomatic way to improve readability, maintainability, and performance

– Me. Just Now

PEP

A PEP is a Python Enhancement Proposal

PEP 1 defines what a PEP is, and the PEP workflow

An important one you'll hear about a lot is PEP 8, the Python style guide

PEP 8

The style guide is a good start to write readable python code

But as the first section just after the introduction says:

A Foolish Consistency is the Hobgoblin of Little Minds

– PEP 8

PEP 20

PEP 20 -- The Zen of Python

Long time Pythoneer Tim Peters succinctly channels the BDFL's guiding principles for Python's design into 20 aphorisms, only 19 of which have been written down.

import this

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

My Setup

What are you building?

Script?

Library/Package?

Application?

Install Python

$ curl https://pyenv.run | bash

$ pyenv install 3.7.3

$ pyenv global 3.7.3

Some common pyenv commands

$ pyenv commands # Show all commands

$ pyenv install --list # Show versions available for install

$ pyenv uninstall # Uninstall a version of python

$ pyenv version # Show the current Python version

$ pyenv versions # Show versions available to pyenv

$ pyenv update # Update pyenv itself

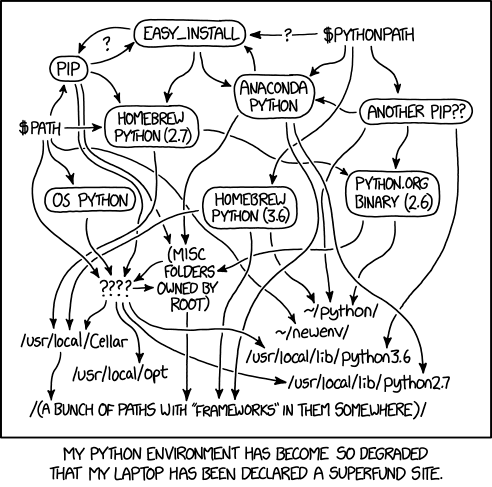

Dependency Management

A problem in every language

Java projects might use gradle to download and isolate dependencies

In python we use pip to download and venv for isolation

Virtual Environment

Every project should exist in a virtual environment

Keeps dependencies from conflicting with each other

Create Virtual Environment

$ mkdir <project> && cd <project>

$ python -m venv .venv

$ . .venv/bin/activate

(.venv) $ python run_command.py

$ ...

(.venv) $ deactivate # when done

$ pyenv virtualenv <project>

$ mkdir <project> && cd <project>

$ pyenv local <project>

Use pip to install third-party packages

(.venv) $ pip install requests # install a package

(.venv) $ pip freeze # print installed packages

(.venv) $ pip show <package> # Show information about package

(.venv) $ pip search <query> # Search PyPI for packages

pip install to your hearts content!

This setup is pretty good, I think

Keeps dependencies isolated to projects

poetry

I've been experimenting with poetry.

It's a dependecy management and packaging tool.

If you're building libraries or applications that are meant to be installed, you should probably use it.

Install poetry

$ curl -sSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/sdispater/poetry/master/get-poetry.py | python

Using poetry

$ poetry new --src my-package

$ poetry add [-D] <package-name>

$ poetry remove <package-name>

$ poetry install

$ poetry build

$ poetry run <command>

REPL

A REPL is a "Read Evaluate Print Loop"

The python interpreter is a REPL

Java 9 comes with a REPL now too (jshell)!

I use the ipython REPL

Install ipython

$ pip install ipython

# or

$ poetry add -D ipython

Daily Workflow

I use the ipython interpreter and the

pudb debugger daily

My daily workflow sees me in ipython playing with data and apis and testing things out before codifying them

Editors/IDEs

I use VSCode a lot, but IntelliJ is also great.

Just need to:

- Install python plugin

- Select the python interpreter to use (in your venv:

./.venv/bin/python)

Let's Talk about Python

I'm gonna go through some quick syntax/features

Keep in mind:

- No semi-colons

- Curly braces aren't used for code blocks

- Indent blocks of code with 4 space characters

- PEP-8 style guide

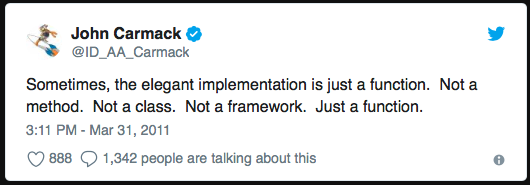

Functions

First-class citizen!

Functions can be passed as around as values!

Parameters are object references passed by value

Example - Function

def foo():

print("Hello, world!")

foo()

> Hello, world!

def sum_things(x, y):

return x + y

def run_func(func, *args, **kwargs):

func(*args, **kwargs)

print(run_func(sum, 1, 2))

> 3

Example - Function

>>> def bar(x, y, default="thing"):

... print(f'x: "{x}" | y: "{y}" | default: "{default}"')>>> bar('hi', 12)

x: "hi" | y: "12" | default: "thing">>> bar('spamalot', 'silly', 'place')

x: "spamalot" | y: "silly" | default: "place">>> bar(y="there", default="boo", x="hey")

x: "hey" | y: "there" | default: "boo"In General

Try to prefer/use pure functions

They make your life easier

Easy to test, and easy to reason about

Classes

First-class citizen!

Classes can be passed as around as values!

Use "magic" dunders for "overriding" like functionality

Support multiple inheritance

Special Dunder Methods

def __init__(self[, ...]):

def __del__(self):

def __repr__(self):

def __lt__(self, other):

def __gt__(self, other):

def __eq__(self, other):

def __add__(self, other):

def __len__(self):

def __getitem__(self):

def __enter__(self):

... etc.

Example - Class

class Door:

def __init__(self, height: int, width: int, is_open: bool):

self.height = height

self.width = width

self.is_open = is_open

def open(self):

if self.is_open:

raise Exception('Door is already open!')

self.is_open = True

def close(self):

if not self.is_open:

raise Exception('Door is already closed!')

self.is_open = False

Example - Sub-Class

class FrenchDoor(Door):

def __init__(self, windows=6, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.windows = 6

def number_of_windows(self):

return self.windows

Loops

Python uses an iterator protocol

Avoid using indicies. They're usually not needed

If you do need indices, use enumerate()

Example - Loop X Times

squares = []

for i in [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]:

squares.append(i ** i)

squares = []

for i in range(1, 6):

squares.append(i ** i)

squares = [i ** i for i in range(1, 5)]

Example - Loop over Sequences

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for i in range(len(colours)):

print('I love the colour {0}'.format(colours[i]))

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for colour in colours:

print(f'I love the colour {colour}')

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for colour in reversed(colours): # Backwards!

print(f'I love the colour {colour}')

Example - Looping With Indices

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for i in range(len(colours)):

print(i, '-->', colours[i])

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for i, colour in enumerate(colours):

print(f'{i} --> {colour}')

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for colour in reversed(colours): # Backwards!

print(f'I love the colour {colour}')

Example - Looping Over Two Sequences

names = ['Bob', 'Sally', 'Jane']

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

min_len = min(len(names), len(colours))

for i in range(min_len):

print(names[i], 'likes', colours[i])

names = ['Bob', 'Sally', 'Jane']

colours = ['red', 'blue', 'green', 'yellow']

for name, colour in zip(names, colours):

print(f'{name} likes {colour}!')

Example - Sorted Looping

colors = ['red', 'green', 'blue', 'yellow']

for color in sorted(colors):

print(color)

colors = ['red', 'green', 'blue', 'yellow']

for color in sorted(colors, reverse=True): # Backwards!

print(color)

A little more advanced...

Example - Loop Until Sentinel

blocks = []

while True:

block = f.read(32)

if block == '':

break

blocks.append(block)

blocks = []

read_32_bytes = partial(f.read, 32)

for block in iter(read_32_bytes, ''):

blocks.append(block)

Example - For Else

def find(sequence, target):

found = False

for i, value in enumerate(sequence):

if value == target:

found = True

break

if not found:

return -1

return i

def find(sequence, target):

for i, value in enumerate(sequence):

if value == target:

break

else:

return -1

return i

Dictionaries

Almost everything in Python is a dict

Effectively using dictionaries is important for pythonic code

Example - Loop Over Keys

novel = {

'title': 'Don Quixote',

'author': 'Miguel De Cervantes',

'pages': 1072,

'ISBN': '978-0142437230'

}

for key in novel:

print(key)# Can also use .keys() to get a set-like view

for key in novel.keys():

print(key)

Example - Loop Over Values

novel = {

'title': 'Don Quixote',

'author': 'Miguel De Cervantes',

'pages': 1072,

'ISBN': '978-0142437230'

}

for key in novel:

print(novel[key])

novel = {

'title': 'Don Quixote',

'author': 'Miguel De Cervantes',

'pages': 1072,

'ISBN': '978-0142437230'

}

for value in novel.values():

print(value)

Example - Loop Over Keys and Values

novel = {

'title': 'Don Quixote',

'author': 'Miguel De Cervantes',

'pages': 1072,

'ISBN': '978-0142437230'

}

for key in novel:

print(key, '-->', novel[key])

novel = {

'title': 'Don Quixote',

'author': 'Miguel De Cervantes',

'pages': 1072,

'ISBN': '978-0142437230'

}

for key, value in novel.items():

print(key, '-->', value)

Example - Construct a Dictionary

keys = ['title', 'author', 'pages', 'ISBN']

values = [

'Don Quixote',

'Miguel De Cervantes',

1072,

'978-0142437230'

]

novel = {}

for i, key in enumerate(keys):

novel[key] = values[i]

keys = ['title', 'author', 'pages', 'ISBN']

values = [

'Don Quixote',

'Miguel De Cervantes',

1072,

'978-0142437230'

]

novel = dict(zip(keys, values))

keys = ['title', 'author', 'pages', 'ISBN']

values = [

'Don Quixote',

'Miguel De Cervantes',

1072,

'978-0142437230'

]

novel = {k: v for k, v in zip(keys, values)}

Example - Counting With A Dictionary

story = (

'peter piper picked a peck of pickled peppers '

'a peck of pickled peppers peter piper picked'

)

counter = {}

for word in story.split():

if word not in counter:

counter[word] = 0

counter[word] += 1

story = (

'peter piper picked a peck of pickled peppers '

'a peck of pickled peppers peter piper picked'

)

counter = {}

for word in story.split():

counter[word] = counter.get(word, 0) + 1

from collections import defaultdict

story = (

'peter piper picked a peck of pickled peppers '

'a peck of pickled peppers peter piper picked'

)

counter = defaultdict(int)

for word in story.split():

counter[word] += 1

Example - Grouping With A Dictionary

colours = [

'red', 'green', 'blue', 'magenta',

'purple', 'brown', 'yellow'

]

groups = {}

for colour in colours:

key = len(colour)

if key not in groups:

groups[key] = []

groups[key].append(colour)

colours = [

'red', 'green', 'blue', 'magenta',

'purple', 'brown', 'yellow'

]

groups = {}

for colour in colours:

key = len(colour)

groups.setdefault(key, []).append(colour)

from collections import defaultdict

colours = [

'red', 'green', 'blue', 'magenta',

'purple', 'brown', 'yellow'

]

groups = defaultdict(list)

for colour in colours:

key = len(colour)

groups[key].append(colour)

Example - Linking Dictionaries

import os

import argparse

defaults = {'username': 'noseworthy', 'debug': False}

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('-d', '--debug', action='store_true')

namespace = parser.parse_args(['-d'])

command_line_args = {

k: v for k, v in vars(namespace).items() if v

}

args = defaults.copy()

args.update(os.environ)

args.update(command_line_args)

from collections import ChainMap

import os

import argparse

defaults = {'username': 'noseworthy', 'debug': False}

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('-d', '--debug', action='store_true')

namespace = parser.parse_args(['-d'])

command_line_args = {

k: v for k, v in vars(namespace).items() if v

}

args = ChainMap(command_line_args, os.environ, defaults)

Improve Clarity

Use keywords and names over positional args and indices

Use namedtuple to add names to tuple fields

Example - Unpack Sequences

person = (

'mike', 'noseworthy', 0x1E, 'https://github.com/noseworthy'

)

first_name = person[0]

last_name = person[1]

age = person[2]

website = person[3]

person = (

'mike', 'noseworthy', 0x1E, 'https://github.com/noseworthy'

)

first_name, last_name, age, website = person

# This is atomic, and easier to read!

Example - Keyword Arguments

# what the heck does this do?

repo_search('noseworthy', 10, True)

# Now it's a little clearer

repo_search(username='noseworthy', limit=10, forks=True)

# It probably searches github for repos owned by

# the user 'noseworthy', returns a max of 10,

# and includes forked repos.

def add_contact(f_name, l_name, age, website):

...

person = (

'mike', 'noseworthy', 0x1E, 'https://github.com/noseworthy'

)

# unpack sequence as positional arguments

add_contact(*person)

def add_contact(f_name, l_name, age, website):

...

person = {

'f_name': 'mike',

'l_name': 'noseworthy',

'age': 0x1E,

'website': 'https://github.com/noseworthy'

}

# unpack mapping as keyword based parameters

add_contact(**person)

Example - Update Multiple States

def fibonacci(n):

x = 0

y = 1

for i in range(n):

print(x)

t = y

y = x + y

x = t

def fibonacci(n):

x, y = 0, 1

for i in range(n):

print(x)

x, y = y, x + y

Example - Clarify Multiple Returns

# Who's a what now? 🤔

tester.runtest()

>> (10, 1, 3, 14)

# 😲 Much Better.

tester.runtest()

>> TestResult(passed=10, failed=1, skipped=3, total=14)

from collections import namedtuple

TestResult = namedtuple(

'TestResult',

['passed', 'failed', 'skipped', 'total']

)

def runtest():

...

return TestResult(passed, failed, skipped, total)

Efficiency

Don't move data around unnecessarily

Cache hits are fast, misses are slow

Use generators instead of loading all data into memory

Example - Sums

def first_n(n)

num, numbers = 0, []

while num < n:

numbers.append(num)

num += 1

return numbers

sum_of_first_n = sum(first_n(1_000_000))

def first_n(n)

num = 0

while num < n:

yield num

num += 1

sum_of_first_n = sum(first_n(1_000_000))

Example - List Comprehensions

result = []

for i in range(10):

s = i ** 2

result.append(s)

sum_of_squares = sum(result)

# list comprehension (clearer, but fills memory)

sum_of_squares = sum([i ** 2 for i in range(10)])

# generator expression (Clear AND fast and space efficient)

sum_of_squares = sum(i ** 2 for i in range(10))

String Handling

Use join, don't use +

Use ''' or """ for multi-line string literals

Two strings next to each other will automatically concat

Example - String Concat

food_items = ['spam', 'sausage', 'eggs', 'bacon', 'toutons']

meal = 'I ate: ' + food_items[0]

for food in food_items[1:]:

meal += ', ' + food

meal += ' for breakfast!'

print(meal)

food_items = ['spam', 'sausage', 'eggs', 'bacon', 'toutons']

meal = 'I ate: {0} for breakfast!'

print(meal.format(', '.join(food_items)))

Example - Multi-Line Strings

import json

json_string = '''

{

"name": "Michael",

"age": 30,

"languages": [

"english",

"python"

]

}

'''

person = json.loads(json_string)

story = (

'The quick brown fox '

'jumped over the '

'lazy dog.'

)

print(story)

>> 'The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.'

Updating Sequences

If updating the beginning of a list, use deque

Example - deque

names = ['sally', 'ann', 'jimmy', 'bobby']

# VERY SLOW - Need to shift everything in the list around

del names[0]

names.pop(0)

names.insert(0, 'sue')

from collections import deque

names = deque(['sally', 'ann', 'jimmy', 'bobby'])

# O(1) time! 🔥 - Double ended queue to the rescue!

del names[0]

names.pop(0)

names.insert(0, 'sue')

Decorators and Context Managers

Advanced features for expert pythonistas

Separates business and admin logic

Clean refactoring tools that improve code reuse

Example - Decorator

import urllib.request

def get_url(url, cache={}):

if url in cache:

return cache[url]

with urllib.request.urlopen(url) as response:

page = response.read()

cache[url] = page

return page

import urllib.request

from decorators import cache

@cache

def get_url(url):

with urllib.request.urlopen(url) as response:

return response.read()

from functools import wraps

def cache(func):

cache = {}

@wraps(func)

def wrapped_func(*args):

if args in cache:

return cache[args]

result = func(*args)

saved[args] = result

return result

return wrapped_func

Use functools.lru_cache

This was added in Python 3.2

Just use this where applicable

Example - Read File

def get_words(file_path):

f = open(file, 'r')

try:

data = f.read()

finally:

f.close()

return data.split()

def get_words(file_path):

with open(file, 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

return data.split()

Example - Locks

import threading

lock = threading.lock()

lock.acquire()

try:

print('Critical Section 1')

print('Critical Section 2')

finally:

lock.release()

lock = threading.lock()

with lock:

print('Critical Section 1')

print('Critical Section 2')

Example - Explicitly Silence Exceptions

import os

try:

os.remove('file.png')

except OSError:

pass

import os

from contextlib import suppress

with suppress(OSError):

os.remove('file.png')

Stop Writing Classes

Some of you are going to want a class for everything

Classes are great, but not everything is a class

Sometimes a class, is really just a function

Truth

Example - Not a Class

class Greeting:

def __init__(self, greet):

self.greet = greet

def say_greeting(name):

print(self.greet + name)

g = Greeting('Hello there, ')

g.say_greeting('Michael')

def greet(greeting, name):

print(greeting + name)

greet('Hello there,', 'Michael')

Empty Classes

# Why!?!

class Flow:

pass

Example - Non-Pythonic Class

class School:

def __init__(self, students):

self.students = students or []

def enroll(self, student):

self.students.append(student)

def class_size(self):

return len(self.students)

...

class School:

def __init__(self, students):

self.students = students or []

def enroll(self, student):

self.students.append(student)

def __len__(self):

return len(self.students)

...

# really just an array...

school = [student1, student2, student3]

Super Trivial Examples

But these do happen

They do obfuscate your code

Use the class level dunders

- __call__

- __len__

- __setitem__

- __getitem__

- __iter__

- etc...

Allows you to use the class with standard operators

Big 'Ol Refactor

Bonus Unsolicited Opinions!

- Don't leave module level code around

- Adopt the style of your project and team, but try to be pythonic otherwise

- Don't put too much in

__init__.py - Use classes sparingly

- Type hints can be useful though I haven't used them much